Posted on December, 1 2023

General Motors continues to build its Ultium Cells battery plant near Lansing as the automotive industry confronts slower-than-expected electric vehicle sales and high capital costs to build them. As it cuts costs, GM is pausing construction at its Orion Township Assembly factory, which was paired with the Ultium factory for over $600 million in state economic development incentives.

General News / Posted on November, 22 2023

Long-awaited guidance from the US Treasury Department that could prevent automakers from buying materials from China will likely resemble regulations aimed at protecting the US semiconductor industry, industry experts told S&P Global Commodity Insights.

General News / Posted on November, 6 2023

ENERGYWIRE | The news that big auto companies like General Motors and Ford Motor are slowing their electric vehicle rollouts has one group a bit relieved: battery-makers.

This nascent U.S. industry has received $58 billion of investment in the year since the Inflation Reduction Act became law, according to Jay Turner, a professor at Wellesley College in Massachusetts who maintains an EV-investment database. That’s far more than any other part of the EV ecosystem. People in the industry say they could use a break from this red-hot streak to catch their breath.

Posted on October, 11 2023 / Author: CAITLIN OPRYSKO

A group of domestic battery stakeholders is also banding together to try and make sure that in all the attention being paid to investing in sustainable supply chains for critical minerals and other materials that go into making batteries, investing in domestic production of the machinery that manufacturers batteries doesn’t fall by the wayside.

— U.S. Battery Machine Builders includes Abbott Furnace, Bechtel Global Corporation, BW Papersystems, Charles Ross & Son Company and Siemens, and argues that a focus on onshoring equipment for everything from extracting critical minerals to assembling batteries will accomplish the same sustainability, economic and national security objectives cited in focusing on the supply chain for the raw materials themselves.

Posted on August, 28 2023 / Author: Daniel Moore

US battery projects have proliferated since the Inflation Reduction Act was enacted one year ago, outpacing other clean energy technologies encouraged by the climate-and-tax law and spotlighting a heavy lift of shifting supply chains from China.

Since August of 2022, when President Joe Biden signed the law, Bloomberg NEF has tracked $72 billion of announcements by automakers, battery manufacturers, and other stakeholders in the electric vehicle supply chain. That includes nearly $55 billion for battery-related projects.

While the industry’s supporters celebrate the progress, they acknowledge the scale of the investment represents the daunting challenge of turning the hype into reality.

Much of the battery supply chain is dominated by China, and the US battery plants sprouting up to supply electric vehicle manufacturing and power grid storage are weighing cheaper costs of imported materials while signing deals with US producers.

“Now is this incredible opportunity in time in our industry,” said Chris Burns, co-founder and CEO of NOVONIX, an Australia-based battery technology firm building a 400,000-square-foot synthetic graphite production facility in Chattanooga, Tenn.

The NOVONIX plant, expected to begin operation next year, will produce at least 10,000 metric tons per year of synthetic graphite for battery cell company Kore Power, and the company’s US workforce has grown to 120 people. It plans to finalize a $150 million grant from the Department of Energy to help pay for a new plant in the Southeast that will initially target 30,000 metric tons per year of production capacity for LG Energy Solution with an option for LGES to buy up to 50,000 tons of the material over a 10-year period.

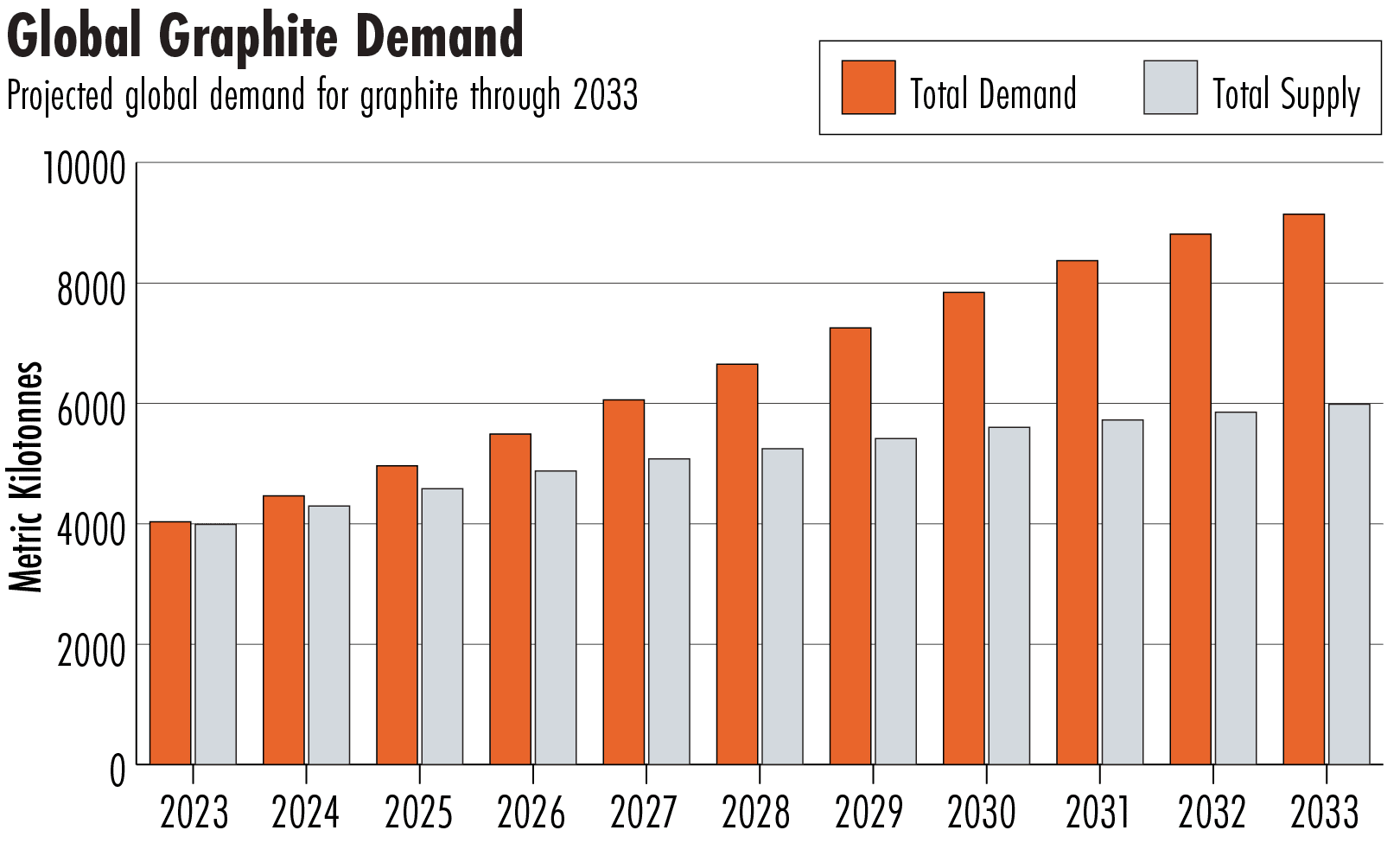

Graphite is an essential material for anodes in lithium-ion batteries, but production is dominated by China. The US funding and permitting regime means production is still being deployed slower than China, which continues to build graphite facilities in one year that are five times bigger and half the cost of those in the US, Burns said.

“We have huge challenges competing with China because of the maturity of their industry, as well as their ability to deploy capital very quickly,” Burns said.

Leveling the Playing Field

The Biden administration and bipartisan members of Congress have sought to level the playing field between the US and China. The battery supply chain spans mineral mining, refining and processing, production of components like cathodes and anodes, and final battery assembly.

In 2021, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act allocated $7 billion to the Energy Department to award grants to companies throughout the battery supply chain. In October 2022, the agency announced $2.8 billion for nearly two dozen companies, including NOVONIX. The DOE plans to announce the second round of funding awards before the end of the summer.

The climate law, enacted in August 2022, included the 30D electric vehicle tax credit for batteries that are assembled in North America and for batteries that source a certain percentage of critical minerals from the US or trade allies. The minimum percentage increases annually to 100% and 80%, respectively, by fiscal year 2029.

This month, the White House reported the US share of global battery manufacturing capacity is projected to almost double by 2030 and have enough capacity to meet US demand for EV batteries.

The climate law was designed to spur companies to invest, and “it’s quite clear it’s working, just based on the sheer number of deals we’re seeing,” said Lauren Collins, a tax and renewables partner at Vinson & Elkins LLP, referring to energy investment broadly. “It seems like every day we’re getting a term sheet or a tax credit transfer deal.”

Targeting Gaps

The DOE’s battery supply chain program has tried to surgically aid companies aiming to fill supply chain gaps, Steven Boyd, the agency’s acting deputy director for battery and critical materials said in an interview. The US has some of the lowest capabilities in processing materials, such as lithium, nickel, and cobalt, as well as graphite and cathode materials needed for batteries, Boyd said.

“Those earlier-stage types of materials and those processing capabilities, that’s really where we think the investments have moved the bar,” Boyd said.

The second round of funding, expected to be about $3.2 billion, will be announced later this summer and could target electrolytes and binders for cells. “As a supply chain, you’re only as strong as your weakest link,” he said.

Some materials buyers in the auto sector remain concerned about higher prices of inputs made in the US and some trade allies compared with China, said Todd Malan, chief external affairs officer and head of climate strategy for Talon Metals Corp.

Talon operates a nickel-copper-cobalt mine in Minnesota and received a $114 million grant from the Energy Department to build a processing facility in North Dakota, covering about 27% of the total cost. Malan also pointed to the 45X Advanced Manufacturing Tax Credit that provides 10% production tax credit for supply chain companies.

“There’s a lot in these laws that have yet to be fully rolled out that will be even more resources to support an ex-China supply chain,” Malan said. “There’s really strong policy, really strong financial support, and we’re seeing a private sector response.”

Policy Decisions

Major policy decisions still have to be made, including how to treat companies that have had experience with China, said Ben Steinberg, executive vice president and co-chair of Venn Strategies’ critical infrastructure group and a former Energy Department official.

The government must also precisely deploy trade barriers to allow the US industry to grow without raising costs for producers down the supply chain. A 25% tariff on imported graphite, for example, has been waived for years to keep costs competitive, but now companies like NOVONIX are ramping up.

“A large majority of these gigafactories will happen in some capacity,” Steinberg said, using a shorthand for large-scale battery factories.

“The question remains whether we will be importing a majority of the materials and the components that make these batteries for electric vehicles and the grid, which is what we’re doing now,” Steinberg said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Daniel Moore in Washington at dmoore1@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Zachary Sherwood at zsherwood@bloombergindustry.com; JoVona Taylor at jtaylor@bloombergindustry.com

Posted on August, 8 2023 / Author: BY ELIOT CHEN

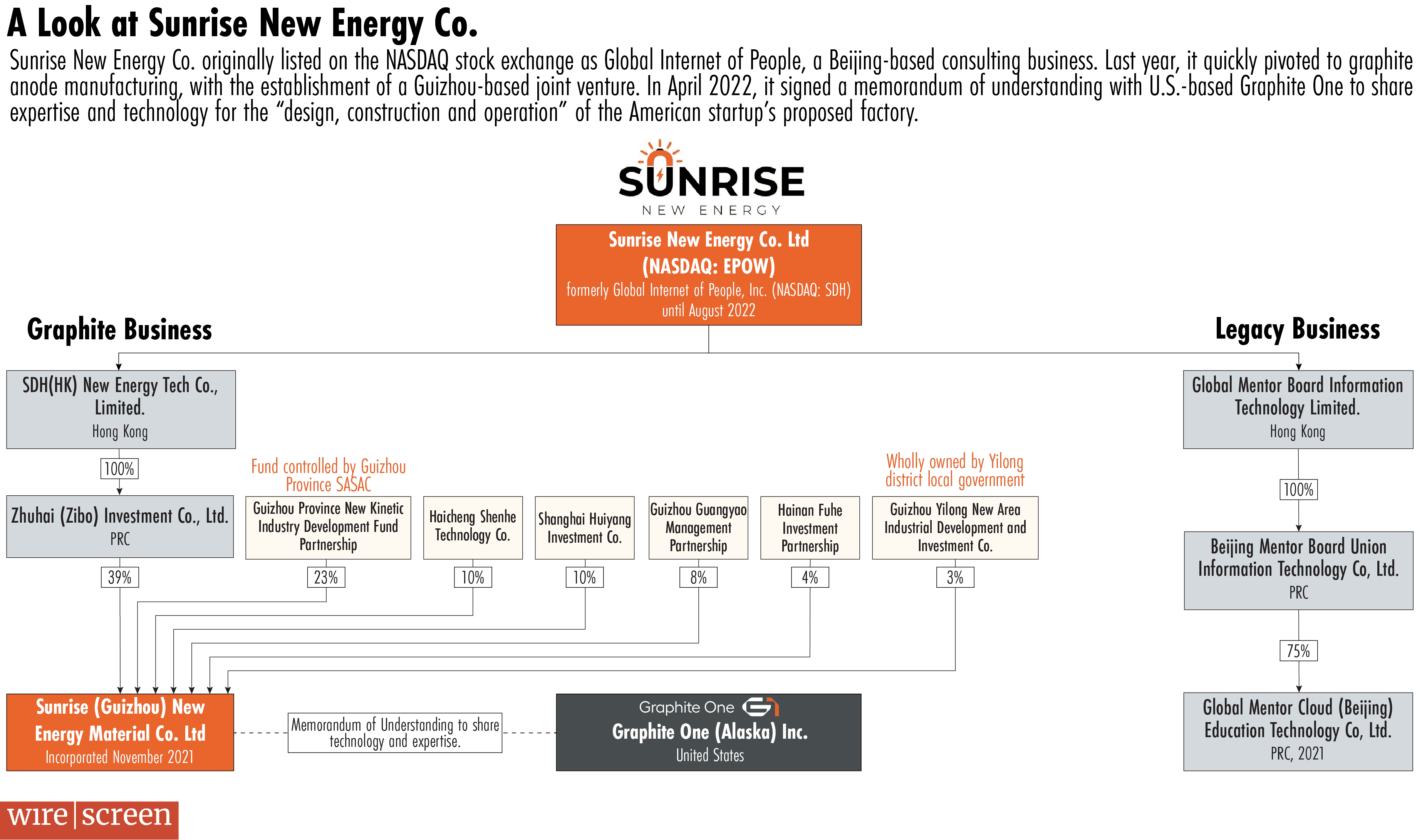

An American mining start-up gained the powerful endorsement of the U.S. Defense Department last month, when it received a $37.5 million grant to develop what could be the country’s largest graphite deposit, close to Nome, Alaska. The company, Graphite One (Alaska) Inc., aims to be America’s first domestic miner of graphite, a mineral that’s vital for producing electric vehicle batteries and is used widely in the defense sector.

But Graphite One’s fortunes will likely depend on the assistance of a familiar rival: China. That’s because a key advisor aiding the company’s plans to build a domestic battery anode factory is a Chinese firm founded by executives with deep ties to China’s battery industry.

In May 2022, Graphite One announced an agreement with Guizhou-based Sunrise New Energy Material Co. — also known as Sunrise Guizhou — that will see the Chinese firm share expertise and technology for the “design, construction and operation” of Graphite One’s proposed battery parts factory in Washington state.

As critical minerals increasingly become a geopolitical flashpoint between the U.S. and China, the apparent conflict of interest at Graphite One could raise uncomfortable questions for the firm and the policymakers who have thrown their weight behind it.

China dominates the mining and processing of graphite, accounting for 61 percent of global mine production and 98 percent of processing, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a research firm. Graphite One’s pitch — amplified by politicians including U.S. Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) — is that it will help America break China’s grip over the industry.

“[Graphite One’s project] will be a secure supply of natural graphite from day one, without the political and the security risks associated with so many projects that are located abroad,” Murkowski said in a Senate speech last month.

Given China’s overwhelming dominance over the graphite industry, it is little surprise that an upstart American firm should require its help. “You have a burgeoning suite of battery anode companies emerging in North America,” says Ben Steinberg, executive vice president at Venn Strategies, a lobbying firm which represents companies in the critical mineral sector, not including Graphite One.

…most fully-formed companies in this industry are in China or touching China in some way, because that’s where the majority of the chemical processing and tech has been developed in the last 10 to 15 years.

Ben Steinberg, executive vice president at Venn Strategies

“But most fully-formed companies in this industry are in China or touching China in some way, because that’s where the majority of the chemical processing and tech has been developed in the last 10 to 15 years,” he says. “I do think there could be value gained in working with those companies if done carefully. The question is how the government will protect the U.S. graphite industry and investments given China’s dominance to date.”

Graphite One (Alaska) Inc. is a wholly owned subsidiary of Graphite One Inc., a listed company headquartered in Vancouver, Canada. The company plans to construct a vertically integrated supply chain, spanning from its Alaskan graphite mine to an anode factory and battery recycling facility to be built in Washington state. Graphite One calculates it will be able to churn out an average of 75 kilotonnes (kt) of anode material per year over the project’s 26 year lifespan. Global demand for anode material is surging alongside the adoption of EVs, reaching 300 kt in 2021, according to the International Energy Agency.

The unusual origins of Sunrise Guizhou add to the intrigue around its technology sharing agreement. While Graphite One has previously described Sunrise as “an experienced battery anode producer,” the Chinese company is in fact a nascent venture, incorporated just months before it landed the agreement.

Public filings and ownership records show how Sunrise’s operations were hastily formalized, beginning soon after an initial public offering in 2021. That February, a Beijing-headquartered company named Global Internet of People Inc. listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange, raising $26.9 million. The company is described in its prospectus as a “consulting company providing enterprise services to small and medium-sized enterprises,” with a “peer-to-peer knowledge sharing and enterprise service platform.”

Global Internet of People’s filings in the leadup to its IPO offer little indication of the company’s experience in the graphite business. But nine months later, in November 2021, it established Sunrise Guizhou as a joint venture via a wholly owned subsidiary, Zhuhai Zibo Investment Co., which held a controlling 51 percent stake in Sunrise. The other investors in the joint venture included a number of privately-owned funds and an investment firm controlled by the local government of Yilong district, in the southern province of Guizhou where the company’s facilities are located, according to data from WireScreen.

Global Internet of People’s directors approved Sunrise’s formation on April 1, 2022. Graphite One announced its technology sharing agreement with Sunrise five days later. Solidifying the parent company’s pivot to batteries, Global Internet of People’s shareholders then greenlit its renaming in August 2022, to Sunrise New Energy Co. Ltd.

Covid was a key driver behind the company’s pivot to graphite, the company’s chairman and CEO, Hu Haiping, said in an interview with The Wire. Prior to entering the consulting business, Hu was a longtime executive at Shanshan Group, parent company of Ningbo Shanshan Co., one of China’s largest manufacturers of battery anodes. The 20-year veteran of Shanshan struck out on his own in 2015, hoping to build an app-based platform that would provide advice to other entrepreneurs. But with small businesses hurting during the pandemic, Hu says interest in the platform fell, leading him back to graphite. In short order, Sunrise recruited a phalanx of veteran engineers and executives with experience in the battery sector.

From a technical standpoint, “having the participation of Hu Haiping is definitely a good sign for Graphite One,” says Albert Li, head of China analysis of Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. “Shanshan has been the leading anode producer in China for about a decade, and Hu was the founder and first general manager of Shanshan Technology. He likely already knows everyone in the supply chain.”

In the months after Sunrise signed its agreement with Graphite One, it also landed orders for its graphite anodes from major EV battery producers including Chinese industry leaders CATL and BYD. The company has rapidly scaled up production: Hu says that after just a year and a half of operations, his company is currently producing 3000 tonnes of anode material per month.

The Chinese government has also become a significant investor, after a fund controlled by Guizhou’s provincial government acquired a 23 percent stake in Sunrise Guizhou for 200 million renminbi ($27.8 million) in June 2022.

For officials in Washington, that could be a cause for concern. In response, Hu says that Sunrise’s management is completely independent, and that the provincial government has never intervened in his company’s daily activities.

There are other advantages for Graphite One in partnering with a relatively young Chinese company, such as Sunrise’s apparent distance from potentially troublesome connections to China’s military. Graphite has important applications in the defense sector, notably in the nozzles of rockets and the exterior coatings of drones, and a number of established Chinese graphite companies have military ties.

Records from WireScreen show that Shanshan Group, for example, controls a subsidiary located in a military civil fusion-focused industrial park. China has pursued the controversial strategy, promoted by President Xi Jinping, which involves fusing the country’s military and civil industrial and technological capabilities. The U.S. government has imposed sanctions in recent years on Chinese firms alleged to be involved in military-civil fusion.

Ownership records reviewed by The Wire found no financial ties linking Shanshan Group and Sunrise, nor ties between Sunrise and military-civil fusion.

As for Graphite One, the DoD’s grant will accelerate its planning process, enabling the company to move up the completion of its feasibility study by a full year.

Securing a domestic raw material supply is one thing — developing the expertise to manufacture complex battery anodes independently is another. Sophisticated factory equipment that China’s producers have spent years honing, notes Benchmark’s Li, are “not something you can copy and paste.”

The path to get there is already narrowing. According to Sunrise’s Hu, U.S.-China political tensions means he’s not sure whether his company will be permitted to export the advanced technology that Graphite One needs to develop its battery anodes. He says that Sunrise’s lawyers are still working out how to continue with the partnership in compliance with Chinese law.

Posted on August, 2 2023 / Author: by HANNAH NORTHEY

General News / Posted on June, 8 2023 / Author: by Bennett Resnik

Policy with bipartisan support is hard to find these days. Luckily, one of them involves the laudable effort to have more U.S.-made products used in federally funded contracts, such as public works and infrastructure projects. For these efforts to thrive and achieve a balanced Buy America policy, the government must reduce bureaucratic complexity, ensure greater transparency and tackle other problems that impede achieving the goals of domestic preference policies. Striking the right balance for Buy America requires a careful consideration of various factors such as economic benefits, job creation, exemptions and waivers and international trade obligations.

Domestic preference laws date back to 1933, though there were earlier laws at the state and local levels that encouraged domestic sourcing. Congress and President Herbert Hoover enacted the Buy American Act during the depths of the Great Depression as part of the National Industrial Recovery Act, creating a preference for U.S.-made products in its procurement of goods and services. Over time, subsequent laws expanded this effort.

In 1978, the Buy American Act was included as part of the Surface Transportation Assistance Act, which extended domestic-preference rules to federally financed transportation projects, such as airports, highways and public transit systems. Today, the Build America, Buy America Act, enacted as part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, requires all federal agencies to ensure no federal financial assistance for “infrastructure” projects be provided “unless all of the iron, steel, manufactured products and construction materials used in the project are produced in the United States.”

These laws became more urgent—but also more complicated—as they were applied to new initiatives. These include President Joe Biden’s 2021 Executive Order on “Ensuring the Future Is Made in All of America by All of America’s Workers” and the Inflation Reduction Act, which includes the Clean Vehicle Credit (an electric vehicle tax incentive under IRS section 30D with battery sourcing requirements).

Each statute is unique and enacted with different requirements and policy goals in mind. The overarching goal, however, is the same: To boost domestic manufacturing and supply chains while increasing U.S. jobs and promoting economic development nationwide. But how does this happen effectively and efficiently?

The Build America, Buy America Act applies “Buy America” to all federally funded infrastructure and public works projects. Though simple in purpose, its requirements can vary depending on the program or project involved. This makes it harder for contractors to navigate the various rules and regulations, which, of course, are meant to minimize waste and misuse.

The Office of Management and Budget—and specifically its Made in America Office – has made progress in implementing President Biden’s January 2021 Executive Order and requirements under the Build America, Buy America Act and has been a strong tip of the spear on domestic preference policy efforts. A remaining core challenge involves agencies determining how to apply domestic-preference guidance to their infrastructure programs and processes.

Critics of Buy America policy argue it increases costs and reduces efficiency. However, these concerns can be addressed by ensuring the policy is implemented in a way that balances the economic benefits with the costs. For example, exemptions and waivers can be provided for goods and materials when strict adherence to the laws is not in the public interest, when the needed materials are not sufficiently available in the U.S. and when using U.S.-made materials would increase a project’s overall cost by more than 25 percent. Timely approval of these requests can help prevent project delays while ensuring the overall objectives of the law are still being met.

These aren’t easy matters. A phased transition, which includes a steady increase in domestic sourcing percentage thresholds to manage supply chains and materials acquisition, is critical to ensuring the viability of any domestic-preference policy.

Additionally, many industries have complex supply chains involving multiple tiers of suppliers and subcontractors. One of the main challenges here is ensuring all required materials and components are made in the U.S. This can be difficult, as many products are made with parts or materials sourced overseas, and it can be challenging to trace the origin of every component in a complex supply chain.

The government should reduce the administrative burden for Buy America compliance to help businesses—especially small- and medium-sized enterprises—compete for contracts without inordinate red tape. Inconsistent implementation of Buy America policies causes undue problems for manufacturers and project sponsors. They become unable to conduct long-term capital project planning, provide investors with peace of mind and predict how the government will treat project bids.

One of the most effective ways to reduce the administrative burden for Buy America compliance is to simplify the requirements. This can include providing clear definitions that apply across the federal government, reducing the number of required certifications and curtailing the amount of paperwork and other administrative tasks.

Greater transparency around the compliance process can also help reduce administrative burdens by enabling businesses to better understand the compliance requirements. Measures could include providing training materials and compliance best practices and ensuring compliance processes are clearly defined and communicated. Technical assistance, such as workshops, webinars or roundtable discussions, would also help.

Most Americans across the political spectrum support Buy America policies and rightly so. The policies support domestic production, enhance national security, certify quality and safety standards and support environmental interests. They promote fair competition by preventing the improper undercutting of domestic prices or distorting market competition.

Inconsistent implementation of Buy America policies, excessive administrative requirements and delays in approving appropriate waivers can hamper the program’s worthy goals. By continuing to address these challenges, the government can responsibly boost U.S. production and jobs.

————-

Bennett E. Resnik is a senior vice president in the Critical Infrastructure Practice at Venn Strategies. The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Venn Strategies or its clients.

Posted on June, 7 2023 / Author: by Steve LeVine

The U.S. has received tens of billions of dollars in electric vehicle and battery investment from around the world, much of it attracted by generous federal subsidies for the industry. In recent weeks, the subsidies survived a partisan attack in Congress. This week we look at the apparent absence of a plan to respond should battery subsidy critics gain power in elections next year.

President Joe Biden has championed his administration’s $250 billion program to build a U.S. battery industry. But, in a recent House vote, all but four Republicans supported repeal of the Inflation Reduction Act, the core of the battery effort.

As it has for decades, the U.S. this year will spend hundreds of billions of dollars on its military. Political support for that spending remains strong, through peace and war, in part because the Pentagon is careful to disburse it across virtually every Congressional district and through 200,000 defense contractors. Critics claim the system encourages waste, but hawks say it helps guarantee a strong military, tying Pentagon budgets to the political benefit of every member of Congress, regardless of their party.

Today, the Biden administration is replicating the strategy in hopes of safeguarding U.S. efforts to create an electric vehicle battery industry that can compete with China’s. Congress approved about $250 billion in spending to support a 10-year buildout of private refineries to process lithium and nickel into battery components, and factories to assemble battery packs to power millions of EVs. So far, the administration is spreading it widely, especially to red states, many of whose members of Congress oppose the battery subsidies but perhaps can be softened up by largesse sent to their home districts: In October, the Department of Energy awarded $2.8 billion in battery industry grants to companies in 14 states under the infrastructure law, $2.3 billion—or 80% of it—to projects in 10 red or purple states.

Among the biggest beneficiaries was Georgia, which has become one of the country’s most active battery hubs. The DOE awarded three battery component companies in the state a combined $515 million in infrastructure grants. Separately, three foreign companies appear to qualify for substantial subsidies for U.S.-made EV batteries under the Inflation Reduction Act, which took effect in November. South Korea’s SK On plans to invest more than $5.8 billion on two battery plants in the state. LG Energy Solution, also of South Korea, is building a $4.3 billion battery plant there, and Norway’s Freyr plans a $1.7 billion battery assembly plant in Georgia.

Industry executives, lobbyists and government officials tell me that the administration strategy has largely worked. Unless opponents capture control of the White House and both houses of Congress in 2024 or 2028, they said, it would be hard to shred the IRA or the infrastructure law. Republican opponents of the IRA might be able to peel off enough moderate Democratic votes to trim or modify either or both measures, but probably not enough to do real damage to either program.

But I wonder why anyone would have absolute faith in the IRA’s longevity given the past three decades of bitter partisanship—most recently the fierce, nearly successful Republican campaign to overturn Obamacare, which survived by single-vote margins in Congress in 2017 and the Supreme Court in 2019. Indeed on April 26, all but four Republican members of the House voted to repeal much of the IRA. This included the entire congressional delegations of Tennessee, South Carolina and Georgia, all the planned sites of massive gigafactories that will benefit from billions of dollars in IRA subsidies.

That suggests the administration’s attempt to inoculate the IRA from partisanship has not demonstrably worked—at least not yet. Support for battery investment is strong in heartland states, but the instinct to attack the works of the opposing party runs deeper when it comes to a big vote in Congress.

I found no one assembling a playbook outlining what to do should things go south and a majority unsympathetic to battery subsidies take power. Nor did anyone seem to think they needed to have such a plan. No one appeared to sense any danger—but there is. “Nothing can be taken for granted,” said Ben Steinberg, executive vice president of lobbying firm Venn Strategies, who advises critical minerals companies.

Battery Industrial Complex

This year’s $858 billion military budget, spread across 420 military installations in all 50 states, is a vestige of the Cold War. Before the 1950s, the U.S. did not maintain a large standing peacetime army and had to scramble when wars broke out. In World War II, the country scaled up its soldiery and armament-making factories virtually from scratch, relying for the manufacture of tanks and warplanes on Ford and General Motors, and demobilized when the fighting was over. But after the Korean War in the 1950s, President Dwight Eisenhower decided to keep the Army and war production economy more or less intact to meet the perceived Soviet threat, and so it has remained. In 1961, Eisenhower famously warned about the emergence of “unwarranted influence” by the “military-industrial complex,” if Americans did not take care to rein it in.

The Biden administration could only dream of burrowing batteries in the national psyche as deeply as the military has managed, even three decades after the end of the Cold War. The federal battery industry programs are doling out large sums, but not at the scale at which the Pentagon spends money. In 2020, the Defense Department spent more than $7.5 billion in each of three states—Mississippi, Alabama and Kentucky—accounting for 6.5%, 6.4% and 5.8% of those states’ gross domestic products, respectively.

By comparison, the administration awarded a $150 million grant to Albemarle, the world’s largest lithium mining company, to help build a lithium hydroxide chemical plant in Kings Mountain, N.C., and $100 million to Applied Materials to build a battery anode plant in an unspecified part of the state. It awarded two grants to support Tennessee’s battery economy: $141 million to Piedmont Lithium to build a lithium hydroxide plant in McMinn County, and $150 million to Novonix Anode Materials to help build a synthetic graphite plant in Chattanooga.

Beyond the federal money, private companies are investing in batteries in some of the same states: Last week, Toyota added $2.1 billion to planned spending on a battery factory in Greensboro, N.C., boosting its investment there to $6 billion. Albemarle and Piedmont both plan to develop lithium mines in North Carolina. In Tennessee, Ford is building a $5.6 billion EV and battery manufacturing complex in Stanton that it calls BlueOval City, and General Motors and LG Energy Solution are building a $2.5 billion battery plant in Spring Hill.

Industry hands perceive little political support for cutting such incentives. The motivations differ, said Jon Evans, CEO of mining company Lithium Americas: Both Republicans and Democrats see critical minerals subsidies as a route to job creation and energy self-reliance for the country, particularly less dependence on the Chinese supply chain, Evans said. Democrats also see lithium as a route to reducing carbon emissions, a popular issue in the party. But either way, he suggested, supporting critical minerals seems to be the patriotic thing. “I don’t have many concerns” about a future Congress cutting IRA funding, Evans said. “Critical minerals are a very bipartisan issue.”

Such reasoning—perhaps a valid reflection of what Republican members of Congress say in calm one-on-one conversation—pays insufficient heed to what they actually do when voting as a tribal group. In the latter settings, some Republican critics have branded the subsidies for such plants as inflationary giveaways to corporations that would build them anyway, and unaffordable given deficits. “If I were in charge, I would repeal the whole awful piece of legislation,” Rep. Scott Perry (R-Pa.), chair of the ultra-conservative House Freedom Caucus, told reporters, of the IRA.

The safest strategy in a world of uncertain politics might be to spend the money as fast as possible while exercising care, and that’s what some industry hands think the administration is doing—shoving money out the door as fast as it can. “I think the administration is judiciously deploying funding from the infrastructure law and the Inflation Reduction Act within their first term,” Steinberg told me. Jigar Shah, head of the DOE’s Loan Programs Office, which stewards more than $412 billion in lending authority for energy projects, told me that any such appearance is false. “Everyone has to meet absolute standards,” Shah said of the loans program. “If they are prepared, we can move them fast. And if they are not, then we give them advice on how to fix their applications.”

But as fast as the process goes, the administration is still likely to distribute only a fraction of the money at its disposal by the end of Biden’s first term. The DOE will probably manage to dole out another $4 billion in battery grants under the infrastructure law before January 2025. Shah, whose program has awarded almost $10 billion in battery grants, including large sums to GM and Nissan, will award more loans, but hundreds of billions of dollars will still be unspent. On top of that will be hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies earmarked for consumers who buy EVs whose batteries were largely made in the U.S. or in countries with which it has a free trade agreement. One page of a hard-nosed pro-battery playbook would advise getting well out in front of the risk of future sabotage by loudly linking local jobs and economic advantage from specific current or future subsidized plants. The next page would hint at the political hell to pay should anyone mess with those subsidies.

Rajesh Swaminathan, a venture capitalist with Khosla Ventures, told me that a single presidential term is simply not long enough to build a battery industry—it requires more time for nurturing. But will it get it? “This is where we lose to countries like China that take a long-term horizon,” Swaminathan said.

Posted on April, 17 2023

When the Department of Energy announced a $200 million

grant to battery maker Microvast Holdings for a plant in

northern Tennessee last October, it seemed like a win-win.

The funds would enable the Texas-based company to

quickly ramp up production of its cutting-edge technology,

and bolster the U.S.’s battery supply chain — a key goal of

the Biden administration’s $1 trillion infrastructure spending

package. In the following months, however, Microvast found itself

embroiled in a political controversy that has left the status of

the DOE grant in doubt.

The dispute stems from Republican lawmakers’ criticism of

the company’s ties to China. In multiple letters to Secretary

of Energy Jennifer Granholm, Senator John Barrasso (R-WY)

and Congressman Frank Lucas (R-OK) have pointed out that

the majority of Microvast’s assets and revenues are in China,

and argued that the “DOE’s actions directly undermine the

United States’ position in its race against China for

technological supremacy.”

The DOE, which did not respond to requests for comment, is

now reviewing the grant, in line with its normal procedures.

Microvast says that despite the scrutiny, it is optimistic that it

will receive the funding due to the merits of the project —

whose location has now switched to Kentucky, and which it

is building in partnership with General Motors.

Can we realistically expect the U.S.

having no exposure to China on

battery development, given their

status in the supply chain and

dominating the sector to date? I think

the answer to that is no.

Ben Steinberg, a former DOE official

who now co-chairs the critical

infrastructure practice at Venn

Strategies.

Whatever the outcome, the episode lays bare the political

liability that connections to China have come to represent for

U.S. companies, while underscoring just how difficult it is for

the government to build up American supply chains in

sectors like battery technology without funding companies

with at least some ties to China.

“We need to go into this eyes wide open, but also with the

recognition that China started down this path many years

before us,” says Ben Steinberg, a former DOE official who

now co-chairs the critical infrastructure practice at Venn

Strategies, a lobbying firm which represents companies in

the sector, not including Microvast.

“Can we realistically expect the U.S. having no exposure to

China on battery development, given their status in the

supply chain and dominating the sector to date? I think the

answer to that is no,” he says. “The question is, are there

good ways for the government and industry to build a

resilient supply chain together that limits risks? The answer

is yes.”

Founded in Houston in 2006, Microvast is run by Wu Yang, a

Chinese American entrepreneur who attended Southwest

Petroleum University in Chengdu and went on to run

Zhejiang Omex Environmental Engineering, a Chinese water

purification company which was acquired by Dow Chemical

in 2006. Wu currently owns 27.5 percent of Microvast,

according to filings.

Microvast’s R&D and manufacturing facility in Huzhou, Zhejiang, China. Credit: Microvast

The company does have an extensive footprint in China,

generating nearly two-thirds of its revenue there in 2022.

Until two years ago, all of Microvast’s manufacturing

capacity was in Huzhou, a city near China’s eastern coast.

The company also operates a 75,000 square foot R&D

center in Huzhou, and owns four subsidiaries in China.

In 2011, Microvast received $25 million from the International

Finance Corporation, the World Bank’s investment arm,

before raising $400 million in a 2017 funding round for one

of its Chinese subsidiaries from two major Chinese

investment firms, state-run CITIC Securities and CDH

Investment. Ying Wei, managing partner at CDH, sits on

Microvast’s board.

Still, the company is now U.S. listed: it went public on

Nasdaq two years ago through a reverse merger with a

special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) called Tuscan

Holdings. Microvast’s shares shot up by over 50 percent

after the October DOE announcement, before steadily

declining since then amid uncertainty about the grant. Its

current market value is around $400 million.

Am I aware of China and U.S. tension?

Sure. Are we the right company they

should be focused on to make their

example? Absolutely not.

Shane Smith, Microvast’s chief

operating officer none. Despite the company’s initial focus on China, Shane Smith,

Microvast’s chief operating officer, emphasizes the

company’s growing presence in Europe and the U.S. due to

increasing demand outside of China — in 2021, the company

completed a Berlin plant, and the company has a new testing

center in Colorado and manufacturing plant in Tennessee.

“Here’s an American company that has just gotten in the

crossfires, that is spending money in the right way to make

the United States electrification supply chain stronger,”

Smith says. “Am I aware of China and U.S. tension? Sure. Are

we the right company they should be focused on to make

their example? Absolutely not.”

The company’s evolution,

Smith says, is reflective of the

broader market, in which

Chinese battery makers like

CATL and BYD have become

global leaders in production

following years of government

support.

“If you were going to try to sell

any kind of battery that you

made before 2010, the only

place you could really sell that

was in Asia, specifically China,

because that was the China

government’s goal was to get going on electrification. And

so you had to build a battery there.” If the company had tried

to build an American presence earlier it wouldn’t have been

successful, he argues, citing the fact that many lithium ion

battery makers in the U.S. went out of business at that time.

The grant to Microvast was one of 21 the DOE has awarded

to battery projects across the country, with money allocated

from the infrastructure bill signed last year. The Microvast

project, which the company expects to create 562 new jobs,

is focused on battery “separators” — the membrane

between the two sides of a battery. The company

manufactures separators with a patented material similar to

that used in bulletproof vests or firefighting garments, thus

“Improv[ing] safety for electric vehicles” and “enable[ing]

faster charging and longer battery life,” according to DOE

grant materials.

The Republican lawmakers’ criticism of the DOE grant to

Microvast centers on fears that the U.S. government will be

funding the development of intellectual property which could

land in Chinese hands, as well as concerns that the DOE did

not conduct adequate due diligence before allocating money

to the company.

Microvast executives, including founder and CEO Wu Yang (center) outside the Orlando

R&D facility. December 10, 2021. Credit: Microvast

Microvast, which opened a second R&D facility in Florida in

2016, maintains that although development of its separator

technology started in China, one of the company’s U.S.

subsidiaries own the IP. It also argues that the DOE is

already familiar with its global operations from past

experience of working together — for example, the

department awarded Microvast $1.5 million in 2018 as part

of a project to fund research on fast battery charging.

“The decision to award a grant to a company with well documented.

ties to the Chinese Communist Party raised red.

flags,” Congressman Lucas, who chairs the House Science,

Space, and Technology Committee said in a statement to

The Wire. “Our concern is much broader than any individual.

company—our primary goal is to make sure that the

Department of Energy is doing its due diligence on everyone.

of these awards, which means conducting appropriate.

investigations and verifying that there are guardrails in place.

that will protect this taxpayer investment.”

In a letter reviewed by The Wire from Kathleen Hogan, a DOE

official, in response to Senator Barrasso’s concerns, she

wrote: “The technology was developed in China and would

be manufactured in the U.S. for the first time, obviating the

typical risk of intellectual property loss and jump-starting

progress toward the Administration’s goal of rebuilding U.S.

manufacturing leadership.”

Big picture, the government should be

wary of any company with reliance on

China, either in manufacturing or

research. Emily de La Bruyère, co-founder of

Horizon Advisorynone Smith, the Microvast COO who is a former submarine officer

in the U.S. Navy, has been reaching out to lawmakers to

dispel their concerns, but he says that none have been

interested in engaging with him.

“China tech issues have become a major focus point of both

political parties. There is a good reason behind that,” says

Fabian Villalobos, an associate engineer at the RAND

Corporation, citing the long history of Chinese IP theft

issues.

But he adds that while there is a degree of risk involved in a

project like Microvast’s, the government should be

considering whether the benefits outweigh the potential

costs. “If part of the risk is IP transfer, either licit or illicit,

then that’s a risk we take on. But the benefit is that we have

a more resilient industrial base because China no longer

dominates battery materials. I believe it is a net benefit.”

Others have a different calculus. “Big picture, the

government should be wary of any company with reliance on

China, either in manufacturing or research,” says Emily de La

Bruyère, co-founder of Horizon Advisory, a China focused

consultancy. “I don’t think we should be letting companies

play both sides. We are only cementing a system of

industrial dependence.”

Microvast, in the meantime, appears determined to keep

playing both sides: In 2022, it obtained a $111 million loan

from a group of lenders led by a Chinese bank to fund

expansion of its Huzhou facility. Smith, Microvast’s COO,

says it remains an “America first” company, but that it is still

approaching China “opportunistically, just like any good

business.”

General News / Posted on April, 13 2023 / Author: By Timothy Cama, Hannah Northey

GREENWIRE | The Biden administration’s climate change agenda has spurred an unprecedented lobbying boom driven by mineral and battery companies in search of incentives for expanding North American operations.

More than 30 of those companies retained lobbying firms for the first time since President Joe Biden took office in 2021, an E&E News analysis of disclosure records found, while many others boosted their lobbying might or greatly increased spending.

The National Mining Association, which had reduced its spending amid the coal downturn, more than doubled its federal lobbying expenditures from 2020 to 2022, when it reached $2.2 million.

The rush to influence lawmakers and agencies is evidence of the challenges and opportunities related to meeting the president’s goal of seeing half of all new cars sold be zero-emission vehicles by 2030. That push requires a mineral and battery production capacity that largely resides abroad — something policymakers are scrambling to change.

“There’s a real frenzy of activity and a genuine excitement in the manufacturing spaces that were very precarious investments a short time ago, said Mike Carr, a former Hill aide and Obama administration official who is now partner at the bipartisan lobby firm Boundary Stone Partners. “So everybody’s scrambling to ensure that their voices are heard.”

Boundary Stone has signed clients including solar cell maker Hanwha Q Cells, battery storage company Antora Energy Inc. and battery maker Form Energy. The firm last year launched the Coalition for American Battery Independence to push for U.S. battery incentives.

Critical minerals, battery and other clean-tech companies have already scored major policy wins during the Biden administration and are now working to secure their vision of how the infrastructure law, the Inflation Reduction Act and other initiatives are implemented.

The Inflation Reduction Act, passed by Democrats under budget reconciliation, includes tax incentives for electric vehicles, but with certain sourcing mandates championed by Senate Energy and Natural Resources Chair Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) to increase domestic production of minerals and other components.

The Treasury Department last month released long-awaited guidance on how to implement those requirements. It’s a document lawmakers, automakers and miners have been eager to shape.

Biden has also invoked a Cold War-era law to boost critical minerals. The Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, appropriates up to $500 million under the Defense Production Act to help U.S. and Canadian companies strengthen mineral supply chains.

Other wins: The Department of Energy got $55 billion from IRA for loans to support and scale up EVs and battery components, and the $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure law included $7 billion to boost domestic battery supply chains.

LG Chem Ltd., Syrah Resources Ltd. and Ioneer Ltd. have all been offered loans or loan guarantees from DOE for various projects. Since 2021, LG Chem has spent $1.2 million in lobbying and Ioneer has spent $250,000.

Many companies are also pushing Biden and Congress to accelerate the permitting process for infrastructure projects, including transmission lines to help meet the administration’s green goals. It’s currently the most prominent energy and environment legislative fight.

And then this week, EPA announced draft car tailpipe emissions rules that could lead to electrification of 67 percent of new sedans, crossovers, SUVs and light trucks.

Ben Steinberg, executive vice president and co-chair of Venn Strategies’ critical infrastructure group, said the focus on mining and EV battery supply chains is part of across-the-board growth in clean energy manufacturing. Steinberg currently leads the Battery Materials and Technology Coalition.

“The mining sector is now part of that story for the first time in the country,” said Steinberg. “It is an exceptional time across many different sectors right now.”

Critical mineral and battery companies have long been lobbying the federal government and were keen on former President Donald Trump’s support for mining.

But the advocacy accelerated with Biden setting climate and manufacturing goals, and has continued as the president’s agenda materializes, said Joe Britton, principal of Pioneer Public Affairs.

“Biden put a clear focus on where he wants to see manufacturing growth, and the emission reduction potential that’s inherent in battery utilization is enormous,” said Britton, former chief of staff to Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.), who has made electrification a priority.

Political prioritization is important, he said.

“Some of these big multinational corporations can build anywhere in the world, and it’s really important for them to hear that this is a priority for the federal government,” said Britton.

“It matters to these companies in a big way when they’re deciding where to build billion-dollar facilities,” he said. “Knowing that there’s durable political support for this manufacturing and job growth really matters.”

Pioneer’s lobbying clients include the Solar Energy Industries Association and the Zero Emissions Transportation Association, or ZETA.

Among the companies that have retained lobbyists since 2021 are Piedmont Lithium Inc., which is hoping to mine lithium in North Carolina. It retained Venn Strategies in 2021 to lobby on matters surrounding mining, processing and manufacturing of lithium, and has paid $360,000.

“Venn Strategies has been very helpful as we develop our projects, given their strategic importance in boosting the domestic production of critical battery materials, and as we move through the grant selection and loan application processes with the U.S. Department of Energy,” said Malissa Gordon, Piedmont’s vice president of government relations.

“Building a robust EV supply chain is a key initiative for the U.S., so there is a lot of opportunity to engage with D.C. stakeholders as the U.S. builds its policies,” she said.

ElementUS Minerals retained the firm Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck last year and has paid it $80,000. The company plans to extract and recycle minerals like rare earths, iron and titanium.

Graphite One, a Vancouver, Canada-based company exploring a graphite mining and processing site in Alaska, retained Capitol Hill Consulting Group’s Kristina Wilcox, a former Capitol Hill aide, in 2021 and has paid the firm $210,000.

US Strategic Metals, formerly Missouri Cobalt, hired Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld last year, and former Rep. Filemon Vela (D-Texas) is part of the team representing the company. US Strategic Metals has paid the firm $120,000.

The lobbying effort is reaching beyond the United States, to include controversial efforts to mine the ocean floor for mineral-rich nodules. Vancouver-based Metals Co., which is hoping to secure permission to mine a swath of the Pacific Ocean seabed, hired Bracewell LLP.

Scott Segal, a partner at Bracewell, said there’s no question that the critical mineral supply chains are turnkey for the clean energy transition and EV battery production will stall without the necessary minerals.

Environmentalists, who oppose deep-sea mining, have expressed alarm with the rush to mine for clean tech and have called for new rules to protect the environment, secure community consent and make sure taxpayers get their due. But the prospects of mining reform in Congress are dim, with Republicans controlling the House and many Democrats on board with more domestic production.

“The challenge for batteries isn’t just one of scale, but one of time,” said Segal. “That’s put the focus on deep-sea mining. That’s why there’s so much interest in it.”

Companies are also keen on the administration’s implementation of the Inflation Reduction Act’s advanced manufacturing tax credit for clean energy and a bonus to the wind and solar credits for equipment that has a certain level of domestic content.

“Manufacturers are sitting there waiting to make multimillion-dollar bets if it comes out the way that they’re looking for,” said Boundary Stone Partners’ Carr.

Posted on March, 31 2023 / Author: BY HANNAH NORTHEY, DAVID FERRIS